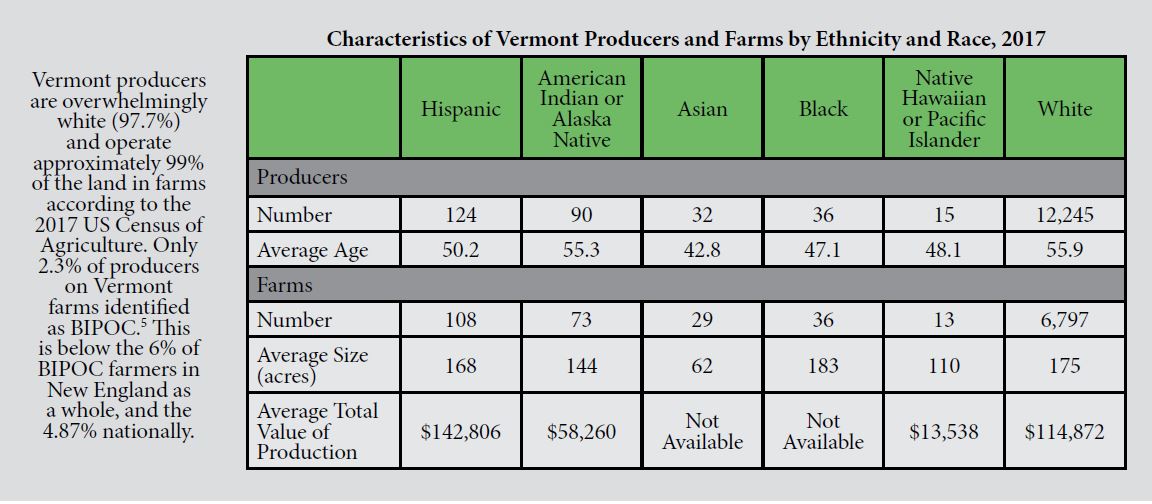

Vermont must work towards racial equity in its food system in order to make the food system truly sustainable for everyone. Equity is “the condition that would be achieved when a person’s race… is no longer predictive of that person’s life outcomes.”1 While food and agriculture can be a source of justice and equity for Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) communities, the Vermont food system is built on hundreds of years of marginalization and inequity. As a result, BIPOC communities experience entrenched and varied challenges throughout the food system. Vermont must build racial equity into all areas of its food system, including processes, structures, initiatives, and practices. Creating a truly sustainable local food system requires more equitable solutions developed by and for BIPOC communities.

Inequities exist throughout Vermont’s food system, from land and farming to food security, the workforce, and beyond. Some of these inequities are rooted in the history and policies that shaped the US food system, which was built on land taken from Indigenous people and further developed with the forced labor of enslaved Black people. Indigenous people, primarily Abenaki, are the original land stewards here and have grown crops, hunted, gathered, and fished across present-day Vermont for over 10,000 years. Europeans brought foreign diseases, waged war, took land, and led the eugenics movement, leading to a significantly reduced and marginalized Abenaki population with little access to their unceded ancestral lands.

Vermont is heralded as the first state to abolish slavery (1777), but the ban only applied to Black individuals over age 21, allowing enslavement of Black youth for another 30 years. Today, many Black people in Vermont—both multi-generation Vermonters and newer community members—still experience marginalization in access to farmland, capital, services, fair wages, food, and other areas of the food system.

Since the 1990s, Latinx farmworkers have supported Vermont’s dairy industry and agricultural economy, but some individuals work under unsafe conditions, with low wages, and/or without full payment. Some Latinx farmworkers lack access to basic human needs like safe housing, health care, and culturally relevant foods.2

The retention and recruitment of BIPOC living, working, and thriving in the state is critical for Vermont’s future.3 It is also crucial that Vermont’s food system acknowledge the significant economic impact of BIPOC in the state—through farming, food, labor, entrepreneurship, innovation, and more. This brief focuses on racial equity in three areas of the Vermont food system: farming success, food security, and the workforce. There are many other fundamental areas of the food system that must be addressed. Ultimately, more focus, financial support, and effort is necessary to conduct a thorough evaluation of the state of racial equity in the Vermont food system and to develop an equitable path forward.