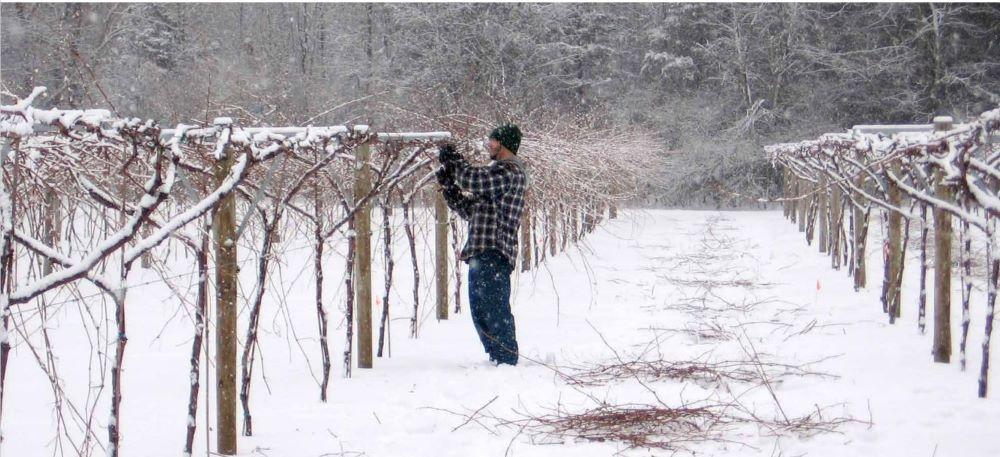

Grapes and wine are a fledgling industry in Vermont with great economic potential and a growing reputation for quality. Grape varieties that tolerate Vermont’s cold winters and produce high-quality wines have only been available since the late 1990s, and in 2016, the value of cold-climate grapes and wines in the United States was estimated at $400 million.To support and sustain Vermont’s share of this growth, the industry must define and maintain standards of quality and regional identity of the diverse wines made in the state. Producers also require organizational and technical support in grape cultivation, business development, and winemaking practices in order to maintain competitiveness.

In the 1990s, Vermont’s grape production was near zero, as wine grapes were not able to survive the cold climate or ripen to produce high-quality wine. Cold-climate grape production began with the introduction of grape varieties developed in Minnesota and Wisconsin, and now breeding programs continue to develop and release new varieties every year. By 2018, approximately 200 acres of grapes were planted in Vermont,1 with total wine value estimated at over $4 million.2 Wines are primarily sold on-site at wineries, with limited restaurant sales and out-of-state distribution. Vineyard growth has been stagnant for the past decade. However, recent growth in “natural wines” made from low-input vineyards with minimal winemaker processing has drawn attention to some Vermont wineries, including from national and international press.

The unique production requirements of grapes and wines require research, education, and business development services. Varietal selection, cold hardiness, training systems, disease management, limited skilled-labor availability, and crop load management are just a few of the challenges grape growers face annually. Likewise, winemaking techniques, access to equipment and financing, and legal considerations are critical to winery success. And capital, financing, branding, and sector development are critical needs to growth of both vineyards and wineries. There is presently limited in-state or regional support from universities or industry groups to support these needs.